Child Development

The process that humans go through from conception to adulthood is both complex and fascinating. Child development refers to all aspects of growth and development from birth to adulthood -physical, social, emotional, language and cognitive.

It is understood that the first 5 years of a child’s life are critical for their development. During this period, they undergo rapid growth and development and this is where the foundations are laid! Most importantly, it is your relationship with your child that influences the way that they learn and develop.

So we have asked the experts from the Baby Lab at Oxford Brookes University to help you understand a bit more about how your child is developing and what you can do to help them.

Foetal movement patterns

Foetal movement

During the embryonic stage, general whole body moves can be observed with no distinctive pattern or sequence. Throughout the foetal stage, the foetus becomes increasingly active, moving its limbs and opening and closing its mouth.

- By 9 weeks, isolated head, arm or leg movements can be observed.

- By 10 weeks, it is possible to see hand-face contact; the foetus can rapidly rotate and change position, stretch and yawn.

- By 12 weeks, finger movements are visible.

- By 14 weeks, the foetus can move the hand at the wrist, independently of movement of the fingers. Growth spurts occurring in the lower body over the 4th month mean that the mother can now feel the movement of the foetus.

- By 16 weeks, foetuses respond to external stimulation, moving the limbs and the trunk. In fact, up to 20,000 movements per day can be recorded in the foetus. Activity further increases during the 5th month and preferences begin to be shown for particular positions.

- By 18 weeks, well-controlled eye movements can be observed, although the foetus cannot see anything as there is insufficient light in the womb.

- The grasp reflex has developed by the end of the 6th month, providing first tactile stimuli. Observations of grasping umbilical cords, touching their own face and sucking thumbs are common.

Foetal sensory development

Auditory development

While in the womb, your baby is already interacting with the external world, and babies are able to respond to a variety of external stimulation. During the 6th month of pregnancy, baby’s hearing system is almost fully developed, and they are able to perceive sounds.

Some studies have also shown that babies are able to recognise music heard in the womb. Similarly, studies have revealed that foetuses are able to distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar nursery rhymes and newborns can recognise nursery rhymes previously heard in utero (D: in the womb). It has been estimated that up to 30% of speech is intelligible in utero. The mother’s voice is a particularly prominent sound, and during this period, your baby will learn to identify their mother’s voice. This is because the mother’s voice is transmitted through the airborne route as well as through body tissue and bone. It is perceived louder and is less subject to distortion. So it is a great idea to talk to your baby and play music to them while in your womb.

Taste and smell development

Babies are also able to taste some of the flavours of the food that the mother eats through the amniotic fluid and those flavours are able to influence the food that your baby will like later on. So aim to eat a balanced and varied diet, and choose fresh fruits and vegetables over salty, processed snacks. This not only helps keep you healthy during pregnancy, but it also sets the stage for your baby to love healthy, diverse tastes

Stages of prenatal development

Germinal stage (Conception to two weeks)

Prenatal development involves three different stages:

1) germinal stage, from conception to implantation in the wall of the uterus at about two weeks

2) embryonic stage, from two to seven weeks; and

3) foetal stage, from eight weeks to birth.

The germinal stage is primarily a period in which the fertilised egg, named zygote, undergoes repeated division into identical copies. Cleavage occurs by the rapid division of the zygote to form the gastrula. The gastrula is a hollow egg-shaped structure which has three layers of cells: the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. These three layers will eventually become the basis for all bodily structures as the process of cell differentiation continues during the embryonic stage.

Embryonic stage (3rd to 8th Week)

Transition to embryonic period occurs upon implantation in the uterus wall. During this period cell differentiation intensifies and 350 different cell types are formed. The ectoderm cells eventually form the skin, the lungs, and the nervous system; the endoderm cells give rise to the lining of the digestive tract, the liver, and associated digestive organs; the mesoderm forms other organs such as the heart and kidneys, blood cells, bones, and tendons. These cells migrate to new locations to give rise to the structural organisation of the individual. There is a rapid differentiation with the formation of limbs, fingers, and major sensory organs. A fluid-filled bag known as the amnion provides a temperature- and shock-controlled environment for the embryo. The embryo is connected to the placenta via the umbilical cord, providing gas exchange and nutrition. By eight weeks, the embryo is about 2 cm long, limb buds have appeared, and eyes and eyelids have begun to form.

Foetal stage (9th Week to Birth)

During this stage many major developments of the nervous system occur and the foetus takes on distinctively human characteristics. Facial features begin to be distinguishable and they can now be identified as male or female. During this stage the foetus is active, moving its limbs and opening and closing its mouth. Months 7 to 9 consist mainly of fatty tissue formation and improved organ functioning.

What can you do to help?

- Remember that during the 6th month of pregnancy, babies hearing system is almost fully developed, and they are able to perceive sounds. So talk to your baby. You can choose a nursery rhyme and read it to your baby every day. You can also play a selection of songs regularly. You will notice that your baby will soon start recognising them.

- It is also very important to eat a balanced and varied diet, and choose fresh fruits and vegetables over salty, processed snacks.

Neonatal reflexes

At birth, babies have limited control over their body. However, they are equipped with different innate survival skills, called reflexes, and they all form part of their early motor development. A reflex is an involuntary motor response to a sensory stimulus.

Rooting

Some of these reflexes are related to early needs such as feeding. ‘Rooting’ for example is a reflex where babies turn their heads towards stimulation such as a touch on their cheek, mouth or lips, opening their mouth and moving their tongue forward.

Sucking

The ‘sucking’ reflex is a reflex where baby’s suck when the roof of the mouth is stimulated. This, combined with the ‘rooting’ reflex, allows new-born babies to already search and suckle for nourishment. The ‘sucking’ reflex is a common reflex in all mammals which enables feeding. The sucking reflex is important to survival, it enables infants to suck and coordinate sucking with swallowing and breathing.

Grasp

Similarly, new-born babies have a grasp reflex, curling their fingers around any object placed in the palm of their hands. However, this reflex fades away gradually over the first few months of development to allow voluntary grasping by the infant. This reflex is a preparation to voluntary grasping.

Babinski

Babies also have a Babinski reflex, which responds to the stimulation of stroking the side of the sole (foot). The reflex causes the babies toes to spread and the big toe extends upwards. Noticeably this is the opposite of the adult’s response to these stimuli.

Early ‘stepping’

Babies also have early ‘stepping’ reflexes; when held over a solid surface babies tend to make stepping motions with their legs extended. The purpose of this reflex is to prepare a baby to walk.

Startle

In addition, babies have a ‘startle’ reflex (also known as the Moro reflex) when they are alarmed or scared; extending their legs, arms and head, clenching fists and crying loudly. Most of these reflexes disappear relatively quickly after birth, as babies slowly gain more control over their own motor actions.

Motor skill development

Gross motor skill development

Gross motor skill development in babies involves large muscles and muscle groups. These tend to develop from the head down in overlapping order. The first development is normally when a baby is able to lift its head from a lying position, at around 1 month of age. Early progress tends to involve the baby using its arms for support, rolling over, supporting some of its own weight with its legs, and eventually even sitting and pulling itself to a standing position. Eventually, motor development progresses so far that the baby will be able to walk, first with support and then alone, completely unsupported, and standing alone easily.

In the weeks and months after birth, babies progressively gain control over movement. Between 4 and 9 months, infants following normal development are able to sit without support and a couple of months later they are able to stand with assistance. By nine months, babies can usually crawl although some move around by shuffling on their bottom. Soon after they will pull themselves to stand upright and, by around 12 months, most babies take their first steps in walking.

Most of the time, this whole sequence of motor development is seen, but in some babies, or in certain cultures, there can be differences in the timing of milestones, and some may even be skipped completely. Some babies in an African Mali tribe, for example, are known to miss the ‘crawling stage’ completely.

Generally, it is thought that babies self-organise their own motor development, becoming more curious and so more daring in using their body to achieve new goals in their surrounding environment. Parental support, improving physical strength, the nervous system and sensory stimuli help to promote development too. This level of motor development requires the integration of action, perception and thought within the baby.

Fine Motor Skills Development

Fine motor skill development is important too, and involves small muscles to allow the baby to make more finely controlled movements to grasp and manipulate smaller objects; like holding a spoon, drawing, or fastening buttons. The first of these appear at around 3 months old when babies begin to show voluntary reaching and grasping. This movement stems from the reflexive palm grasp and develops into the use of a voluntary ‘pincer grasp’, providing the baby with more control and voluntary action, for example holding a pencil, holding cutlery and feeding oneself, turning pages of book etc.

Postural control and balance

Signs of postural adjustments in response to environment can be found from birth. Newborns make postural adjustments of their head in response to a visual display of optical flow. Furthermore, some studies have found that 5- to 13-month-olds adjust their postures while being in a moving room, even if some of them were not yet able to sit alone, showing that vision and motor responses are closely linked.

Between 4 and 6 months of age, babies' balance and movement dramatically improve as they gain use and coordination of large muscles. But it is not until babies start standing alone and walking that their touch control and balance shows a significant change. Different studies have shown that touch control develops through standing experience. The more standing experience a baby has, the less force they would apply to the surface, and consequently, their body sway would decrease.

What can you do to help?

- Making your baby play on their tummy will help them strengthen their back, shoulder, arm, and hand muscles.

- Playing games such as “pat-a-cake” or "The Itsy-Bitsy Spider" with your baby will help them to improve their hand coordination.

- Shifting your baby's positions frequently will help your baby learn to play in a new position, such as on their side. This will challenge their motor skills in different ways and help them to develop.

- Let your baby do things on their own. This allows them to practice their motor skills and promotes independence.

- Try letting your baby balance their feet on your thighs and let them bounce up and down.

Visual Development

Early limitations of sight

We now know that babies watch the world very intently, and use vision to inform them of their environment much earlier than previously thought. Their eyesight is relatively poor upon birth but improves rapidly over the first few months of life, and their visual acuity (D: visual sharpness) approaches that of an adult by 8 months of age, even though it will not be fully developed until age 6. Young babies have quite poor contrast sensitivity, and can only distinguish patterns that contrast greatly. This is due to the immature cones (light sensitive cells) in the fovea of their eye; they are a different size, shape and distribution than cones in an adult eye. Babies also have a very poor colour vision for the first few months of their life, but development is extremely fast so that after 2 or 3 months of life their colour vision is similar to that of an adult.

Face bias

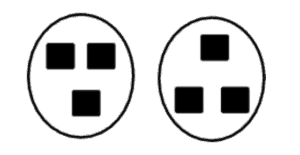

Despite some of these early sight limitations, babies are strongly drawn to faces from birth; preferring to look at things that have the ‘top-heavy’ structure of a human face, such as in the figure on the left compared to the figure on the right.

Specialisation of human faces occurs over the first year of life; at 6 months of age, babies are able to distinguish within many different categories of faces, including even different species such as monkeys. However, adults and 9-month-olds are not able to tell them apart at all: two different monkeys will be treated as the same. This is a sign of infants’ specialisation on human facial features. Accordingly, infants will be better at distinguishing human faces and worse at distinguishing other species.

Picture Perception

Picture perception in two dimensions is also an area of development for babies. Surprisingly, even very young babies are able to recognise people and objects in 2-D from photos and drawings, much the same way as an adult would. However, most infants continue to attempt to explore with their hands a picture, attempting to treat them as real objects

Auditory Development

Early auditory perception

Auditory development occurs from a very early age with newborns and even prenatal foetuses relying heavily on sounds. Although the faintest sound that a newborn will respond to is still 4x louder than the faintest sound that is detectable by an adult. Adult hearing levels only begin to be reached when a child is between the ages of 5-8 years. Newborns responses to sounds are characterised by ‘auditory localization’; the newborn will turn towards the sound. Slow head turning means that newborns can best localise and respond to continuing sounds for several seconds. Infants often perform very well in being able to distinguish patterns of sound e.g. detecting small differences in human speech

Musical perception

Both infants and adults show very similar responses to music perception. It has been found that infants (as argued for adults also) prefer to listen to a consonant(D: stable tone combinations) pieces of music rather than dissonant(D: unstable tone combinations ones. In addition, infants show sensitivity to temporal sequences(D: pace at which a section of music is played; for example, infants will listen longer to Mozart minuet with the ability to identify when unnatural pauses have been added. Infants are also able to detect changes in the order of a melody, which they have been familiarised with previously. Infants often show a response to ‘rhythm’ in music by ‘bouncing’ in time with lively music.

Taste, Smell and Cross-Modal Perception

Taste and smell

From an early age, newborns experience different tastes and smells, even apparent in prenatal foetuses. Newborns experience very early exposure and dependence on certain tastes and smells. It has been found that even a two-week old infant could differentiate their mothers smell from a different woman and orientated longer towards the familiar smell.

Cross-modal perception

Cross-modal perception refers to experiences involving interactions between two or more different sensory modalities. For example, infants are able to recognise and discriminate objects they have explored with their hands (set of rings) or mouth (pacifier), even without previously seeing them. Infants often combine information from two or more sensory systems. A very early example of this is infants turning towards a sound they can hear, suggesting that they expect the sound to be associated with a visual occurrence or object

Audio-visual integration

Already by 4-month-old, infants are able to integrate audio and visual stimuli, making relatively fine-tuned discriminations; for example, babies show a preference to look towards a video when sounds of impact coincide with a hopping animal 'landing' rather than the video where they coincide with the animal in mid-air. They can even discriminate between videos where lip movements are in sync with the recorded speech and out of sync.

What can you do to help?

Your baby’s sensory system started developing in the womb and some of their senses, such as hearing, are already well-developed at birth. This development will happen automatically and you probably can’t make your baby’s sensory system develops faster. However, you can enrich this process by

- Exposing them to different scents whilst telling them what they smells.

- Playing rhythmic hand games such as “pat-a-cake” and "open shut them" to strengthen their eye-hand coordination.

- Making music together with toy instruments.

- Massaging them.

- Laying out different textured objects such as carpet squares, stacking cups, squishy bath toys, foam shapes, mildly abrasive sandpaper; whilst describing each one as they touch them for a fun tactile experience.

- Introducing your baby to a great variety of food, choosing lots of fresh fruits and vegetables.

Recognising other people

Abilities at birth

At birth, babies already have highly developed abilities to recognise familiar voices and smells. Both voice and smell are important in the early recognition of familiar people, usually the baby’s parents and other members of the family. So, in real life, babies normally have information from all their senses to help in identifying important people in their lives even though their sight is not fully developed

Recognising voices

Babies learn to recognise their mother's voice before they are born and will respond to the sound of their voice in the womb. After they are born, they soon link their mother's voice, smell and appearance

Recognising faces

Newborn infants are attracted to faces because of their particular properties and so they spend a lot of time looking at and learning about the faces of the people they see every day. As adults, we tend to be much better at being able to tell apart different human faces than animal faces. However, at 6 months, infants are equally good at discriminating human faces and Macaque monkey faces as they are still learning about the specific properties of human faces. By the time they are 9 months old and have learned much more about the faces of people they come into contact with, infants have lost their ability to discriminate the faces of Macaque monkeys and they can only reliably tell human faces apart. But by this time they are able to make fine-grained discriminations among human faces and to recognise individual people who they see regularly

Imitating other people

Early imitation

Babies can imitate specific actions almost immediately after birth – as early as 42 minutes old. They can imitate lip or tongue movements and can distinguish between two types of lip movement (mouth opening and lip pursing) and between straight tongue protrusion and protrusion to the side

Functions of imitation

Early imitation is thought to have a number of functions. It allows very young babies to engage socially with other people and also helps babies identify particular individuals who behave in specific ways. Imitating the actions of someone else helps a baby to learn about familiar games, such as ‘peek-a-boo’. Babies also respond very positively when their actions are imitated by someone else

Smiling and social recognition

Early smiling

At about 6 weeks of age, the first social smiling appears. At this age, babies begin to smile when they see familiar people, especially their faces. Smiles are not restricted to visual stimuli. Babies will also smile to voices, particularly their mother's familiar voice.

Smiling and social interaction

From about three months, smiling is truly social and reciprocal in that the baby's smile is now synchronised with the smiles of familiar adults. The baby discriminates between familiar and unfamiliar people, smiling more readily to the former but, at this age, there is no fear of strangers. Smiling, like imitation, is a very strong social signal for adults who find the smiles of a young baby and a readiness to imitate very alluring. Smiling and imitation, therefore, play a key role in ensuring that babies and adults spend long periods in social interaction because both infant and adult find interaction to be a rewarding and positive experience that they want to repeat over and over again. These periods of social interaction are important because they provide parents, older siblings and other family members with an opportunity to develop a close emotional bond with the baby and for the baby to develop a bond with family members. They also provide an opportunity for family members to learn more about their baby and for the baby to learn more about them

The 'Still Face' paradigm

Babies expect familiar people to interact with them and they react very noticeably when someone does not interact as expected. This is shown in the ‘still-face procedure', which has 3 phases. In the first, mothers are instructed to interact normally with their infant. Then, in the next period, they are instructed not to respond as normal and to adopt a still face with a neutral expression. Finally, mothers resume their normal pattern of responsive interaction. During the still-face phase, infants typically decrease the amount of looking and smiling to the mother. They rapidly return to their normal pattern of looking and smiling as soon as mothers interact naturally again. This shows how tuned in young babies are to the fact that someone is interacting with them and also how much the behaviour of the baby is affected by the response of the person with whom they are interacting. This study was carried out with mothers but babies are equally sensitive to the way that other people in the family interact with them

Development of Attachment

What is attachment?

Attachment is a strong, long lasting, emotional bond that develops between a baby and other people who play an important part in the baby's life. Attachment grows out of the baby's early interactions, many focusing around caretaking and close physical contact. Early attachments will be to members of the baby's family circle, usually the mother, father, brother and sisters and sometimes grandparents or other close relatives

Why is attachment important?

An attachment figure provides a secure base from which the developing infant can explore the world and periodically return in safety. From an evolutionary perspective, staying close to a familiar adult will protect a young child from harm while enabling learning and discovery. The emotional attachment of the baby also provides a model on which all other relationships are based and a secure attachment in infancy will pave the way for secure and successful relationships in adulthood.

Separation anxiety

Around the age of 8 months, babies become very distressed when they are away from a familiar family member and they see a stranger. This is known as ‘separation anxiety’. Studies carried out in the 1950s showed that babies and young children, who were separated from their parents, became very distressed. Short periods of separation are soon forgotten as soon as the parent returns but long-term separation, for example by a period of illness in hospital, can have serious consequences such as social withdrawal. Thanks to research on separation, parents of babies and young children are able to spend as much time as possible with them during a hospital stay so that normal patterns of interaction are maintained and the child continues to feel emotionally secure

The 'strange situation'

The way that babies react to a stranger, when there is no reassuring adult nearby, gives an indication of how well they are attached to a close family member. This can be tested using the 'strange situation' which has been developed to look at the attachment between a mother and their baby. This test involves leaving a 12-month-old alone with a stranger for a few minutes. This is likely to provoke a strong reaction - usually crying - but when the mother returns and has a cuddle, the infant happily returned to play. This kind of pattern is shown by the majority of infants but some will show a different reaction, such as ignoring the mother’s return, which may indicate the lack of a strong attachment between infant and mother

Development of the self-concept

Self-recognition

Young babies, like almost all animal species, do not recognise themselves when they look in a mirror. Being able to recognise oneself in a mirror is thought to be evidence of possessing a concept of self. Having a concept of self in infancy is the starting point for developing the sophisticated sense of self that can be seen in older children and adults. This sense of self ultimately allows humans to reflect on their role in the family and other groups

Rouge removal task

One way to test whether children recognise themselves in a mirror is to make a mark on their face and see if they attempt to remove it

In the ‘rouge removal’ task, a small amount of rouge is surreptitiously placed on a child’s face. Then the child is allowed to look in a mirror. Some infants as young as 15 months’ notice the strange mark on their face in their reflected image and reach up to remove it, and by the age of 24 months, all normally developing children will respond in this way.

Recognising photographs

Infants will also recognise themselves in photos but they do not seem to be able to do this reliably until around the middle of the second year. Interestingly, they often recognise other familiar people (such as parents and siblings) in photographs and videos before they recognise themselves in the same images.

What can you do to help?

- Talking to your baby will help him/her to recognise you. Although vision is still developing after birth, your baby has excellent hearing and soon learns to recognise the sounds of individual people’s voices.

- Babies find faces fascinating and they soon learn when you are reacting to what they are doing. React to what your baby is doing. Smile, when they smile, makes sounds when they do. Your baby will soon learn about the kinds of things you do together and will anticipate. This helps your baby learn about the world, as well as learning about you and developing a special relationship.

- Babies are good imitators. If you stick your tongue out, your baby will be able to copy you in the first days after birth. Imitation helps babies find out about the world and the special things that you do will help your baby recognise you.

- Interacting with your baby in a positive and predictable way, and reacting to what your baby is doing, will help form an attachment to you.

Interacting with other children

Spending time with other children

Babies cannot choose who they spend time with and the majority of their time is spent with the people who look after them. However, once babies have become toddlers they tend to spend more time with other children. In this section, we look at how toddlers develop relationships with other children

Between the ages of 2 and 5 years, children spend less time with adults and increasing amounts of time with other children. They often have to interact with children whom initially they do not know as they spend time in playgroups or at nursery and engage in social activities such as attending a birthday party.

Awareness of gender

The preschool period is a time when children begin to show an increased awareness of gender. By the age of 3 years, children can accurately label children as boys or girls and they are already showing a positive bias towards same-gender children. They tend to choose play partners and friends of the same gender as themselves and they also regard children of the same gender as being more similar. In one study, 5-year-olds consistently judged same-gender classmates as more similar to themselves than opposite-gender classmates. Interestingly, this feeling of similarity according to gender decreases as children grow older

Siblings

Children who have a younger sibling have an ideal opportunity to learn about caring for others. Birth order is important because older siblings are often encouraged to care for their younger siblings who, in turn, learn to co-operate in these ministrations. Pre-schoolers who have a younger sibling will often comfort them if they show signs of distress. Older sisters are particularly likely to engage in prosocial behaviour. The caring attitude of an older sibling towards a newly arrived younger sibling is strongly affected by the mother’s preparation for the arrival of the baby. When mothers discussed the feeling and needs of the newborn with an older child, that child was more nurturing towards the new baby. Parental influence on this kind of behaviour is very important.

Self-regulation

An important social skill for children to develop during the preschool years is self-regulation. This is the ability to actively control levels of arousal and emotional response to challenging situations. Children's ability to regulate their own behaviour and to respond in a socially appropriate manner is a very important skill for developing social competence and avoiding social problems such as falling out with friends or becoming socially isolated. One of the most common forms of socially undesirable behaviour is physical aggression. During a peer group observation of 21-month-old children in a laboratory for only 15 minutes, 87% participated in at least one conflict with another child. Children’s ability to self-regulate increases significantly over the toddler period as they understand more about the causes and consequences of their own behaviour. In part, this increasing understanding develops with increasing cognitive ability but parents have an important influence on the extent to which young children regulate their own behaviour. Positive parenting, involving the use of indirect commands and reasoning to induce compliance as well as the more general fostering of children’s independence, supports the development of self-regulation. Indirect commands are important because they give the child a greater sense that they are making a choice to carry out an action. Most children want to be helpful and giving them a chance to show this is a positive experience for both them and their parents. So, for example, if parent says that they need help to tidy away toys this gives the child an opportunity to come and help rather than being told directly to tidy their toys.

Friendships

What is a friend?

During the preschool period, many children come into contact with their peers in playgroups and at nursery. At the start of this period, another child is seen as a friend if the two children play together regularly. Children choose to spend time with other children who want to play in a similar way to themselves. In general, pre-schoolers are attracted to other children who are similar to them in some way and, in addition to similarities in behaviour, children tend to choose playmates who are similar in age and gender. Making friends is important for young children because not only does it give them someone to play with but it also gives them a sense of self-worth. Children’s view of themselves is affected by how other children interact with them. Knowing that other children like them and are their friends will increase their self-confidence and sense of belonging to a group

Interacting with friends

By the age of three and a half years, children behave differently towards their friends and other children who they know but have not been singled out as friends. They engage in more social interaction, more initiation of interaction and in more complex play with friends. They also show more positive social behaviours, including cooperation, with friends than with non-friends. A key component of friendship even at this young age is reciprocity. In cases where two children independently nominate each other as friends, they are likely to spend more time together. More friendships tend to be reciprocal as children move through the preschool years.

Falling out with friends

Friendships are often volatile in the preschool period because children are still developing self-control and they tend to react immediately to situations. There tend to be more conflicts between friends than with other peers but presumably this is because friends spend much more time together than non-friends. However, friends make more use of negotiation and taking time out in order to resolve conflicts than do non-friends, and conflicts between friends are more likely to be resolved to mutual satisfaction. After conflicts are resolved, friends will tend to stay close to each other and to carry on interacting whereas disputes between non-friends usually end in separation.

Social problem-solving

Prosocial behaviour

Prosocial behaviour is voluntary behaviour that is intended to help someone else. It is important that children are encouraged to develop prosocial behaviour as this will make them better able to get along with other children. Once children go to school, considerate behaviour towards other children is actively encouraged and is normally part of the school ethos. However, well before children are explicitly taught to engage in prosocial behaviour at school, there is evidence that they will act in a kindly way towards others, for example, by sharing toys or food or comforting a child who is crying. Children who observe a generous or helpful model are more generous and helpful themselves. Preschool children are more likely to model the prosocial behaviour of the adults who care for them over extended periods and so parents provide important models for interaction with others.

Developing trust

We learn much about the world from our direct experience and this kind of direct learning is very important throughout development. However, a lot of what we learn also comes from second-hand experiences - from what we read in books, see on television or hear from other people. In order to learn effectively, children need to discover the people they can trust to give them reliable information. By the age of 3, children can distinguish between someone who has previously given them accurate information and one who does not know the answer. By the age of 4 years, they are able to choose between someone who gave the correct answer and someone who gave an incorrect answer. Pre-schoolers are more likely to trust someone they know rather than someone they don’t know, providing that person does not give them inaccurate information. They also show a preference for information that is independently provided by a number of different people rather than a single person.

What can you do to help?

- Learning to interact with other children is an important first step in learning how to cope in social situations. Giving your child the chance to meet other children is important for social development.

- Your child will learn a lot about how to cope in social situations from what you do. Encouraging your child to talk things through and explaining why some behaviours are not appropriate will help your child to do the same.

- It is normal for young children to be physically aggressive with other children and they often ‘fall out’ with their friends. Encourage your child to say sorry when they hurt another child and to talk through a disagreement rather than being aggressive.

- Encouraging your child to be independent and to make choices will make it easier for them to control their own behaviour.

- Parents can also influence how children learn to share and be kind to other children. They will copy the helping behaviour they observe in adults and older children.

The development of play

Early play

The earliest play takes place between babies and the people who look after them. Young babies take delight in playing games such as ‘peek-a-boo’ and ‘give-and-take’ with adults or older children. Such games are important for developing early social abilities and reinforcing the bond between a baby and the immediate family. Babies enjoy repeating the same games over and over again. This helps them become familiar with the games and to learn their own part in them. Once babies know exactly what is expected in a game they may engage in 'teasing' or 'showing off' in which they deliberately carry out the wrong action or exaggerate it.

Physical play

Preschool children spend more time in physical play than any other kind. This involves activities such as running, chasing, skipping, jumping, rolling, falling and sliding. This kind of physical activity peaks in the preschool years. Typically boys show higher rates of physical activity than girls. Studies show that physical activity brings many positive benefits including better mental and physical health and it helps children to develop their motor skills and to remain at a healthy weight.

Sex differences in play

One of the most notable differences between the play of boys and girls is in their preference for particular toys. Girls tend to be more attracted to dolls and domestic toys whereas boys tend to prefer vehicles and weapons. Almost certainly these preferences for particular toys come about from a combination of inborn preferences and observation of other children and adults. These preferences are likely to be reinforced by the fact that, by the age of 3, girls usually prefer to play with other girls and boys with other boys. Boys tend to play in a more physical way than girls, engaging in more active, rough-and-tumble and sometimes physically aggressive interactions while girls tend to talk to each other more and to be more nurturing.

Pretend play

Pretending with objects

Towards the end of their second year of life, infants begin to use objects to pretend in what is known as 'symbolic play'. For example, they may pretend to drink out of an empty beaker or push a toy car along the floor, with accompanying sound effects. Often this play takes place with an adult or older child who can engage in shared pretending in which child and adult move from the real into an imaginary world. From this perspective, pretend play can be seen as an important social activity in which children can explore different social roles – such as parent or teacher - and develop their imagination. Symbolic play becomes increasingly complex over the next year or so and 2-year-olds can interpret pretend actions as though they have actually happened. For example, if pretend milk is spilt they will spontaneously wipe it up.

Fantasy play

In the preschool years children's pretending moves away from actions with objects towards more elaborate and extended play in which they act out their everyday activities such as being taught at nursery school, going shopping or going to the hospital. This kind of play, which invariably involves at least, one other child and often several, helps children understand the different perspectives of other children as well as allowing them to explore possible worlds. Being aware of the perspectives of other children is the starting point for developing empathy. Fantasy play of this kind becomes increasingly complex as children move through the preschool years and it tends to peak at around 6 years of age.

What can you do to help?

- Playing games like ‘peekaboo’ or giving and taking objects with your baby will help your baby to learn about the sequence of actions in the game. As your baby becomes familiar with a particular game, you can vary it slightly. Babies find these kind of games fun and they will want to play them over and over again. Play these simple games helps babies’ cognitive and development and helps with the understanding of words that are related to these activities.

- Many children show a preference for particular toys and some of these may be typically preferred by boys or by girls. Young children are very aware of what other children, like them, prefer to play with and they want to do the same. Although preferences for particular toys are affected by fashion and culture there do seem to be in-built differences between boys and girls. So make sure your child has a range of toys to play with but don’t be surprised if boys prefer to play with toy cars and girls prefer to play with dolls.

- Young children use play to explore the world. When they are little they want to find out about objects and how they work. When the get a bit older they want to explore familiar and unfamiliar situations, such as going to school or the shop or visiting the dentist. Acting out helps children to understand more about events and also more about other people. Encouraging pretend play will help children’s cognitive and social development and it can also help them understand a new situation that they are about to experience for the first time.

Early speech perception

Speech Perception

The human language involves different sound combinations associated with arbitrary referents, organised according to a complex grammatical structure. This allows the production of an infinite number of sentences and an ability to communicate with one another

From birth, babies possess incredible abilities for perceiving speech. Newborns are able to tell apart languages having different rhythmic patterns, for example, English and Japanese. They are also able to distinguish between stress patterns, for example, a word stressed in the first syllable, such as "doctor" versus a word stressed in the second syllable, like "guitar". Furthermore, at birth, babies have the capacity to discriminate between the sounds of any language. However, adults do not have this same ability, since they are already specialised in their own language. They are often unable to hear sound distinctions that occur in other languages but not in their own.

Between 6 – 12 months, babies start to specialise in the characteristics of their native language. During this period infants' ability to discriminate contrasts that are present in their language increases, and at the same time their ability to discriminate contrasts that do not occur in their language decreases. For example, by 6 months of age, infants are able to tell apart languages belonging to the same rhythmic class such as Catalan and Spanish if they are learning one of these languages. In fact, they are even able to distinguish between two variations of the same language, for example, British versus American English, if they are English-learning infants. However, by 9 months, as adults, infants stop being able to discriminate sounds that do not exist in their language; but they get better at distinguishing the sounds of their own language. For example, while 6 month-old English and Japanese infants can distinguish between a /r/ and a /l/ (Read: an –ar- and an –l- sound, as in the words “loot” and “root”), by 9 months, only the English-learning infants are able to do it, Japanese infants become unable to distinguish between them because that contrast does not occur in their language, so the words “loot” and “root” would be perceived as the same by them. It is also by 9 months that infants become sensitive to the sound sequences that are allowed or not in their native language. For example, in English the sound /t/at the beginning of a syllable can be followed by /r/ as in the word "train" but not by /l/, /n/, or /m/, accordingly "tl" "tn" "tm" are sequences that are not permitted in English. Different studies have shown that by 9 months of age infants prefer to listen longer to sequences that are ‘legal’ in their language compared to sequences that aren't. In fact, infants also show a preference for sound sequences that occur frequently in their language compare with sequences that occur less frequently.

The first words

Finding Words

From birth, infants are immersed in speech, hearing thousands of utterances that do not include systematic marks of where word boundaries are. For example, while listening to a foreign language, words tend to blend into one and it is very difficult to distinguish each individual word.

Therefore, in order to learn the words of their native language, infants have to solve a very challenging task, that is, they have to discover what is and is not a word. Years of research have shown that to start finding word boundaries, infants exploit different regularities of their language very early in life. For example, in English, 90% of words are stressed on the first syllable, and infants use this rhythmic regularity to find word boundaries so that infants learn that it is very likely that a stressed syllable will indicate the beginning of a word. Furthermore, infants also use their knowledge about sound sequences to find words; in this case, sequences that are not allowed in the language will be a good indicator of a word boundary. For example, we know that the sequence /tm/ is not allowed in English, so if you find this sequence this means that the /t/ is the ending of a word and /m/ is the beginning of another word as in the sequence "hot muffin"

Word comprehension

Some beginnings of word comprehension have been found as early as 5 months of age. There are some studies showing that 5-month-olds are able to recognise their own name. By 6 months of age, infants show evidence of comprehending very frequent words like “daddy” and “mummy,” or “hand” and “feet”. By 9 months, infants understand up to 50 words, most of them are food related words, toys, body parts, or routines. Understanding of words increases slowly at first then ‘spurts’ for most children. At 16 months, the word comprehension range is 70 – 270 words.

Towards word production

Early on, babies start producing sounds. At first, these vocalisations do not contain meaning or refer to anything specific. This period is called babbling. From birth to two months, infants make sounds to express discomfort and distress as well as vegetative sounds, such as burping, sneezing, coughing and sounds that are related to physical activity or bodily functions. During this period, speech sounds are very rare. From 2 to 4 months babies begin to use sounds for more directly communicative purposes. They coo and laugh when people are talking to them or smiling. These sounds are produced singly at first but then they start to appear in sequence. By 6 months infants start producing isolated syllables, such as "ba" "ta" or "ma" and by 8 months they produce repeated syllable sequences, like "bababa" or "tatata". It is not until 10 months of age that infants are able to produce syllable sequences containing different consonants, such as "pata" or "bada"

Around 11 to 13 months it is possible to string sounds into recognisable words. However, at this stage, much modification takes place, including word simplification or reduction, reduplication of vowels or substitution of consonants. For example, a baby will say "nana" for "banana", "mama" instead of "mummy" or "gock" for "sock". There is considerable variation in age when first words are produced, some babies start producing their first words by 11 months and some others by 18 months. At 16 months, the word production range is between 0 – 130 words. Production increases slowly at first then ‘spurts’

What can you do to help?

- Babies start learning their language in the womb, and very quickly they start learning all the relevant properties that will help them understand and produce words. The best thing that you can do to help your baby learn is to talk, talk and talk:

-

- Narrate the day as it evolves and describe all the activities that take place.

- Read to your baby. It is never too early to start reading; you can even start when you are pregnant.

- When you read picture books, tell them what they are looking at so they associate the words with objects.

- Tell your baby elaborate stories.

- Use television, computers and noisy toys sparingly. While there are some good educational programs which can be beneficial to your baby, TV shows and computers don't interact with or respond to babies. Interaction and responsiveness are the two catalysts that babies need to learn language.

From words to sentences

Early word combinations

At the beginning babies start producing one-word utterances, this period is known as the one-word stage. The words used at this stage are nouns for the most part, like "mummy", "car", "water" etc. Infants use these sentences primarily to obtain things they want or need. Most children start combining words into simple utterances by the time that they are two years old, although some children will be doing so well before their second birthday.

Between 16 and 20 months, children start what is known as the two-word stage. During this period, children are able to combine words and produce two-word utterances. Some examples of these utterances are "mummy come", "eat grape", "go park", "my teddy” and "more juice"

By 24-36 months children enter into the telegraphic stage. During this stage, children are able to produce longer utterances. However, these utterances will be characterised by a lack of function words, such as "the", "a" "this", "will", "would" "and" "but"etc. The telegraphic stage is so named because it is similar to a telegram; which used to contain just enough information for the sentence to make sense. This stage contains many three and four word sentences. Some examples of sentences in the telegraphic stage are “Mummy eat carrot”, “What her name?” and “He is playing ball.”

The beginnings of grammar

In addition to combining words and making longer sentences, children need to learn some other rules. For example, an "s" at the end of the noun means plural, as in the word "shoes" or it can also mean possession, as in "Mike's hat". The endings of a verb indicate tense, for example, "ed" indicates past tense as in the word "showed" or "ing" indicates progressive as in the word "doing". Between 28 and 36 months children are able to produce ing- forms and s-plurals. By 36-42 months, children start using irregular past tense, for example "me fell down" and possessives, like "man's book". A few months later, between 40 and 46 months, children are also able to make sentences using regular past tense, like "she jumped" and third person regular present tense, like "Oliver runs". By 42 to 52 months, children can produce third person irregular forms, for example "she does" and they can also contract auxiliaries and use the shortened form of the verb "to be" for example "she's ready" or "they're coming".

Another important thing that children need to learn is that word order can change the meaning of a sentence, for example, "the dog is biting the man" versus "the man is biting the dog". The evidence suggests that by 24 months children are already sensitive to changes in word order and they use word order as a guide to meaning.

Vocabulary Development

Vocabulary development

Vocabulary rapidly increases during the second year of life, growing from around 20 words at 18 months to around 200 at 21 months. New words are mainly object names, such as "mummy", "chair" or "dog", but also include action names like "look" or "gone", state names, such as "red" or "lovely" and some function words like "there" or "more". The language of a 3-year-old is largely understandable to adults, even outside the family. By this age their vocabulary comprises around 1,000 words, the length and complexity of utterances have increased and they are able to carry on reasonable conversations, although this tends to be rooted in the immediate present. By 5 years, a child is able to understand and express complex sentences and their use of language is very similar to that of an adult. Estimations indicate that a 6-year-old child has a vocabulary of nearly 11,000 words, which rises to 20,000 at the age of 8 and then doubles by the age of 10 years

What can you do to help?

During their second year of life, your child will start combining words to produce sentences. You can help them develop this by

-

- Giving them lots of opportunities to talk. Include them in your conversations to give them a chance to chat.

- Responding to their words with more words. If they yell “car!”, then say “Yes, it is a red car like Grandmas’s one”.

- Ask them questions. Two-sided conversations will help your child to practice their new skills, so pose questions to your toddler that call for more than a yes or no answer.

- Devoting your full attention. Stay focused when she’s speaking. If you get distracted, they will too.

Cognitive development

What is cognitive development

Cognitive development refers to the development of children’s abilities to understand the world, to think and to solve problems. It covers a very wide range of skills that begin in infancy and continue into the school years. Children vary in their rates of cognitive development right from birth but individual differences become more obvious when children go to school and they are formally assessed to see how they compare with other children. Reading, writing and mathematical ability are all part of cognitive development as well as more general abilities like reasoning and problem solving.

Categorising the world

What is categorisation?

One of the most basic cognitive abilities is grouping objects into categories. For example, when you look at different cats you can tell one cat from another, and yet you consider them all to belong to the single category of ‘cat’. The ability to form categories is important because it allows people to form expectations about a new member of a particular category. So, if you already know about cats and you see a new cat you will know how it is likely to move, what it likes to eat and what sound it will make. The ability to form categories also enables us to reduce memory load by storing together the information about members of a category. So, for example, you don’t need to remember for each individual cat that is has four legs and a long tail. The ability to form categories is so fundamental to our thinking that it is thought to form the basis for all our thinking and cognitive processing.

Categorisation in infancy

Experimental studies have shown that infants, who are a few months old, can form categories of different objects and animals. These studies are carried out using photos and comparing the amount of time that babies spend looking at new examples of animals that fall within the same category or a different category. One study showed that 3- and 4-month-old infants can form a category for cats and distinguish it from dogs, birds, horses and tigers. Studies of slightly older infants show that they pay particular attention to the shape of an animal's head when looking at new animal photographs although, for real animals, movement patterns are also likely to be important. Infants' abilities to categorise become more sophisticated over the next few months as they develop an awareness of how different features, such as four legs and a tail or wings and beak, tend to occur together. Once infants begin to learn words, they are then able to use names as a way of grouping into a category. For example, if they learn that a new animal is a 'bird' they will be able to group it with other birds that they already know about.

Understanding objects

Object permanence

Another important aspect of early cognitive development is understanding that objects exist even when they are out of sight. Over the first 18 months of life infants show a series of developments in the way they respond to objects. If you put a cloth over an object, young infants, below 8 months of age, will not search for the object even if they see the object being covered up. Around 8 months they will reach for and retrieve an object if it is partially covered and they can see part of the object. Around 9 months they will uncover a fully covered object.

These changing responses to objects occur very reliably in babies’ early development and they are an indication of their changing ability to process information about the world. The ability to look for an object that is out of sight and to locate it is called ‘object permanence’

Looking in the wrong place for an object

Although by the age of 9 months, babies can uncover an object when they see it being covered up, they continue to make mistakes about where an object has been hidden. If an object is hidden in a particular place – such as behind a cushion – on several occasions a 9-month-old baby will be able to retrieve the object. However, if the same object is then hidden in a new location – such as a different cushion – the baby will look for the object in the first location. Strangely enough, this will happen even though the baby has watched the object being hidden in the new location.

By the time babies reach 12 months of age they will successfully look in a new location for an object. These changes in the ability to keep track of an object’s location are clear evidence of cognitive development over the first year of life. Although experience is important for cognitive development, a major reason why babies show an increase in their ability to understand the world is that their brains are continuing to develop after they are born. In fact, their brains will continue to develop all through the preschool and school years and recent research show that brains are still developing in adolescence.

Understanding numbers

Adding and subtracting in Infancy

Further evidence of babies’ cognitive abilities comes from their surprising ability to tell the difference between one and two and two and three objects. They can also keep track of what happens when one object is taken away or one added. This ability is present in babies as young as 5-month-old and it was first demonstrated in a study using puppets.

The babies first saw an empty stage. Then they saw a hand appearing and placing a Mickey Mouse doll on the stage. Then a screen came across to hide the doll so the babies could no longer see it. The hand then reappeared and placed a second doll behind the screen so that there were two dolls. Then the screen dropped and the infants saw either one Mickey Mouse doll or two. As there has originally been one doll, and then another one was added, there should have been two dolls. The researchers carrying out the study wanted to see whether the babies who saw two dolls would behave differently from babies who saw only one doll.

Babies who saw only one doll – an impossible event - looked significantly longer at the stage than the babies who had seen two dolls – the expected event. In another version of this study, the babies initially saw two dolls being placed on the stage and then saw one doll being removed, leaving one doll behind. In this case, babies looked longer at the impossible event of two dolls.

This study shows that, even in the first months of life, babies are able to understand that 1 object + 1 object = 2 objects and 2 objects – I object = 1 object. This is important evidence of the cognitive abilities that even young infants have.

Learning to count

Children begin to develop some awareness of numbers in the preschool years. Initially, they learn some number names but will not always be able to say them in the correct order for counting. When they first begin to count objects they have to learn that saying numbers in the correct order is essential to finding out how many objects there are. They also have to learn that each object has to be counted once and only once and that when this has happened the final number in the counting sequence is the total number of objects. These are difficult concepts but very important for understanding simple addition and subtraction since learning to count correctly is key to understanding what numbers really mean. Counting with objects is also used in the early stages of learning about addition and subtraction. Children can learn the answer to a simple subtraction sum such as 7 – 5 by counting out 7 objects, then taking away 2 objects and counting again to see how many are left.

What can you do to help?

- Babies are constantly learning and you can give them opportunities to explore new objects and see new events. You can hide an object and then uncover it or turn an object round to that your baby can see it from different angles. Babies are fascinated by object movement so roll a ball across the floor or suspend an object so it can rotate. Watching objects and also playing with them gives babies the opportunity to learn at their own pace about the properties of objects and how they behave. Don’t be surprised if they want to see actions with objects repeated over and over again as they gradually learn more about what to expect.

- Being able to sort things into categories is very important for much early cognitive development. You can help by getting your child to find things that are the same, starting with simple categories such as dogs or cats and then moving onto more difficult categories, such as colour or shape, as children begin to understand these concepts.

- Learning to count is an important foundation for mathematical understanding for pre-schoolers. Practice counting objects as that make it easier to understand what numbers mean.

Appearance, Fantasy and Reality

Appearance and reality

As adults, we are usually able to tell whether something is real or not. However, this is a difficult concept for children who will carry on learning about the difference between things and people that are real and things and people that are only pretend, right through the preschool years. Children also have to discover that things are not always as they appear to be.

In one famous study, young children were shown a piece of sponge that had been carefully painted to look like a rock. They were allowed to squeeze the "rock" and discover that it was actually spongy. Then they were asked two questions, one about what the object looked like and one about what it actually was. The majority of three-year-olds gave a similar answer to both questions and replied that the object looked like a sponge and was really a sponge (or sometimes, that the object looked like a rock and really was a rock). However, four-year-olds were able to give the correct answer, that it looked like a rock but was really a sponge

This shows that, around the age of 4 years, there is an important change in children’s cognitive ability. They are able to start taking more than one possibility or dimension into account. In the case of appearance and reality, they are able to recognise that something can look like one thing but actually be something else.

Fantasy and reality

Young children often invent complex fantasies, and they often come across fantastical creatures like Santa Claus, elves and cartoon characters. Traditionally the view had been that children confuse the boundary between fantasy and reality but more recent studies suggest that pre-schoolers can reliably distinguish between things that they imagine and those that are real. They understand that you can see, touch and act upon a real object but you cannot do any of these things to an object that is imaginary. However, the boundary between the real and the not-real can be blurred for pre-schoolers. Children aged between 4 and 6 years were asked to imagine that there was either was a friendly rabbit inside a real box or a scary monster. Almost all of the children knew that the imagined creature was not real. However, when left alone, a number went to look inside the box to see what was inside. This suggests that, although pre-schoolers can distinguish between fantasy and reality, they are tempted to believe in what they have imagined

Social cognition

During the preschool period, children begin to develop an understanding of the difference between their own perspective and that of other people. They begin to realise that what they can see may not be the same as what will be seen by someone else viewing the same scene from a different vantage point. They also begin to understand what other people think, feel and want and how this will affect their behaviour. This knowledge is referred to as social cognition. As the term suggests, social cognition can be viewed as being on the boundary of social and cognitive development.

Theory of mind

One very important development that takes place between 3 and 4 years is acquiring what is known as a 'theory of mind'. This involves understanding that what someone else knows or believes about something may not be the same as what they think or believe. This can most easily be seen in what children understand about someone’s mistaken belief – a belief that hinges around the fact that the other person does not have some crucial information that the child does. Initially, children do not understand that the other person might not know everything that they know and they expect other people to have the same information that they do. In contrast, if children have a theory of mind they will realise that someone else may not know everything they know and that this will affect how they will behave in a particular situation.

The ‘Smarties’ test

There are now a number of classic false belief tasks that have been developed to test whether preschool children have a theory of mind. One test involves a tube of Smarties. Children are shown the tube and asked what is inside. Naturally they say ‘Smarties’. When they are shown the contents of the tube they see it actually contains pencils. They are then asked what another child, who has not seen the tube before, will think it contains. The correct answer is, of course, Smarties since this is what the appearance of the tube suggests. However, most 3-year-olds say that another child will think the tube contains pencils even though there is no way of telling this without looking inside. By the age of 4, most children are correctly able to say that another child will think the tube contains Smarties and have realised that another child will not know what they know.

The Sally-Ann test

Another theory of mind task - the Sally-Ann task – involves a story acted out with two dolls. One doll called Sally, hides a marble and then goes for a walk. A second doll, Ann, then moves the marble while Sally is still away and so cannot see what has happened. Children are asked where Sally will look for the marble when she comes back. As Sally did not see the marble being moved she will look in the original location but 3-year-olds say that she will look in the new location. 4-year-olds are able to say that Sally will look in the old location as they have realised that, although they know where the marble really is, Sally does not

What can you do to help?

- Understanding that other people do not always see or feel the same as you or know the same things you know takes the time to develop and is an important aspect of learning for pre-schoolers. You can help by talking about different perspectives in a simple way, such as the kind of food everyone likes or who can see what. You can also get your child to think about why someone might be happy or sad and it is useful to explain why you feel a particular emotion. This can help children to develop empathy and also explain their own feelings.

- You can help your child understand more about what is real by talking about the difference between real and pretend version of things, for example, pretend food versus real food and toys versus pets. You can also talk about real versus imaginary people so that children begin to understand the difference between the two.

- You can explore the differences between what is real and what is ‘only pretend’ through pretend play although don’t be surprised if your child finds it difficult to explain the difference between play and pretend. This a difficult concept that your child will still be learning about after starting school.